Image:ShakespeareCandidates1.jpg, alt=Portraits of Shakespeare and four proposed alternative authors, Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Bacon

Bacon is a type of salt-cured pork made from various cuts, typically the belly or less fatty parts of the back. It is eaten as a side dish (particularly in breakfasts), used as a central ingredient (e.g., the bacon, lettuce, and tomato sand ...

, Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby gai ...

, and Marlowe Marlowe may refer to:

Name

* Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593), English dramatist, poet and translator

* Philip Marlowe, fictional hardboiled detective created by author Raymond Chandler

* Marlowe (name), including list of people and characters w ...

(clockwise from top left, Shakespeare centre) have each been proposed as the true author.

poly 1 1 105 1 107 103 68 104 68 142 1 142 Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (; 12 April 155024 June 1604) was an English peer and courtier of the Elizabethan era. Oxford was heir to the second oldest earldom in the kingdom, a court favourite for a time, a sought-after patron of ...

poly 107 1 214 1 214 143 145 142 145 104 107 104 Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

rect 68 106 144 177 William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

poly 1 144 67 144 67 178 106 179 106 291 1 290 Christopher Marlowe (putative portrait)

poly 145 143 214 143 214 291 108 291 107 179 144 178 William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby

William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby, KG (1561 – 29 September 1642) was an English nobleman and politician. Stanley inherited a prominent social position that was both dangerous and unstable, as his mother was heir to Queen Elizabeth I un ...

The Shakespeare authorship question is the

argument

An argument is a statement or group of statements called premises intended to determine the degree of truth or acceptability of another statement called conclusion. Arguments can be studied from three main perspectives: the logical, the dialectic ...

that someone other than

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

of

Stratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon (), commonly known as just Stratford, is a market town and civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon district, in the county of Warwickshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It is situated on the River Avon, north-we ...

wrote the works attributed to him. Anti-Stratfordians—a collective term for adherents of the various alternative-authorship theories—believe that Shakespeare of Stratford was a front to shield the identity of the real author or authors, who for some reason—usually social rank, state security, or gender—did not want or could not accept public credit. Although the idea has attracted much public interest, all but a few Shakespeare scholars and literary historians consider it a

fringe theory

A fringe theory is an idea or a viewpoint which differs from the accepted scholarship of the time within its field. Fringe theories include the models and proposals of fringe science, as well as similar ideas in other areas of scholarship, such a ...

, and for the most part acknowledge it only to rebut or disparage the claims.

Shakespeare's authorship was first questioned in the middle of the 19th century,

[; ; ; ; .] when

adulation of Shakespeare as the

greatest writer of all time had become widespread. Shakespeare's biography, particularly his humble origins and

obscure life, seemed incompatible with his poetic eminence and his reputation for genius,

[.] arousing suspicion that Shakespeare might not have written the works attributed to him. The controversy has since spawned a vast body of literature, and

more than 80 authorship candidates have been proposed,

[.] the most popular being

Sir Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both n ...

;

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (; 12 April 155024 June 1604) was an English peer and courtier of the Elizabethan era. Oxford was heir to the second oldest earldom in the kingdom, a court favourite for a time, a sought-after patron of ...

;

Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe (; baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), was an English playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the Elizabethan playwrights. Based upon the ...

; and

William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby

William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby, KG (1561 – 29 September 1642) was an English nobleman and politician. Stanley inherited a prominent social position that was both dangerous and unstable, as his mother was heir to Queen Elizabeth I un ...

.

Supporters of alternative candidates argue that theirs is the more plausible author, and that William Shakespeare lacked the education, aristocratic sensibility, or familiarity with the royal court that they say is apparent in the works. Those Shakespeare scholars who have responded to such claims hold that biographical interpretations of literature are unreliable in attributing authorship, and that the convergence of

documentary evidence used to support Shakespeare's authorship—title pages, testimony by other contemporary poets and historians, and official records—is the same used for all other authorial attributions of his era. No such

direct evidence

Direct evidence supports the truth of an assertion (in criminal law, an assertion of guilt or of innocence) directly, i.e., without an intervening inference. A witness relates what they directly experienced, usually by sight or hearing, but also p ...

exists for any other candidate, and Shakespeare's authorship was not questioned during his lifetime or for centuries after his death.

Despite the scholarly consensus, a relatively small but highly visible and diverse assortment of supporters, including prominent public figures,

[.] have questioned the conventional attribution. They work for acknowledgment of the authorship question as a legitimate field of scholarly inquiry and for acceptance of one or another of the various authorship candidates.

Overview

The arguments presented by anti-Stratfordians share several characteristics. They attempt to disqualify William Shakespeare as the author and usually offer supporting arguments for a substitute candidate. They often postulate some type of

conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, is a secret plan or agreement between persons (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder or treason, especially with political motivation, while keeping their agree ...

that protected the author's true identity, which they say explains why no documentary evidence exists for their candidate and why the historical record supports Shakespeare's authorship.

Most anti-Stratfordians suggest that the

Shakespeare canon exhibits broad learning, knowledge of foreign languages and geography, and familiarity with

Elizabethan

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personifi ...

and

Jacobean court

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordance ...

and politics; therefore, no one but a highly educated individual or court insider could have written it. Apart from literary references, critical commentary and acting notices, the available data regarding

Shakespeare's life

William Shakespeare was an actor, playwright, poet, and theatre entrepreneur in London during the late Elizabethan and early Jacobean eras. He was baptised on 26 April 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon in Warwickshire, England, in the Holy Trinit ...

consist of mundane personal details such as

vital record

Vital records are records of life events kept under governmental authority, including birth certificates, marriage licenses (or marriage certificates), separation agreements, divorce certificates or divorce party and death certificates. In some ...

s of his

baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

, marriage and death, tax records, lawsuits to recover debts, and real estate transactions. In addition, no document attests that he received an education or owned any books. No personal letters or literary manuscripts certainly written by Shakespeare of Stratford survive. To sceptics, these gaps in the record suggest the profile of a person who differs markedly from the playwright and poet. Some prominent public figures, including

Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among t ...

,

Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

,

Helen Keller,

Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

,

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies explained as originatin ...

,

John Paul Stevens

John Paul Stevens (April 20, 1920 – July 16, 2019) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1975 to 2010. At the time of his retirement, he was the second-oldes ...

,

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (born Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, later Philip Mountbatten; 10 June 1921 – 9 April 2021) was the husband of Queen Elizabeth II. As such, he served as the consort of the British monarch from El ...

and

Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is consider ...

, have found the arguments against Shakespeare's authorship persuasive, and their endorsements are an important element in many anti-Stratfordian arguments.

At the core of the argument is the nature of acceptable evidence used to attribute works to their authors. Anti-Stratfordians rely on what has been called a "rhetoric of accumulation", or what they designate as

circumstantial evidence

Circumstantial evidence is evidence that relies on an inference to connect it to a conclusion of fact—such as a fingerprint at the scene of a crime. By contrast, direct evidence supports the truth of an assertion directly—i.e., without need ...

: similarities between the characters and events portrayed in the works and the biography of their preferred candidate; literary parallels with the known works of their candidate; and literary and hidden allusions and

cryptographic

Cryptography, or cryptology (from grc, , translit=kryptós "hidden, secret"; and ''graphein'', "to write", or '' -logia'', "study", respectively), is the practice and study of techniques for secure communication in the presence of adve ...

codes in works by contemporaries and in Shakespeare's own works.

In contrast, academic Shakespeareans and literary historians rely mainly on direct documentary evidence—in the form of

title page

The title page of a book, thesis or other written work is the page at or near the front which displays its title (publishing), title, subtitle, author, publisher, and edition, often artistically decorated. (A half title, by contrast, displays onl ...

attributions and government records such as the

Stationers' Register

The Stationers' Register was a record book maintained by the Stationers' Company of London. The company is a trade guild given a royal charter in 1557 to regulate the various professions associated with the publishing industry, including print ...

and the

Accounts of the Revels Office—and contemporary testimony from poets, historians, and those players and playwrights who worked with him, as well as modern

stylometric studies. Gaps in the record are explained by the low survival rate for documents of this period. Scholars say all these converge to confirm William Shakespeare's authorship. These criteria are the same as those used to credit works to other authors and are accepted as the standard

methodology

In its most common sense, methodology is the study of research methods. However, the term can also refer to the methods themselves or to the philosophical discussion of associated background assumptions. A method is a structured procedure for bri ...

for authorship attribution.

Case against Shakespeare's authorship

Little is known of Shakespeare's personal life, and some anti-Stratfordians take this as circumstantial evidence against his authorship. Further, the lack of biographical information has sometimes been taken as an indication of an organised attempt by government officials to expunge all traces of Shakespeare, including perhaps his school records, to conceal the true author's identity.

Shakespeare's background

Shakespeare was born, brought up, and buried in

Stratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon (), commonly known as just Stratford, is a market town and civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon district, in the county of Warwickshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It is situated on the River Avon, north-we ...

, where he maintained a household throughout the duration of his career in London. A

market town

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village or city. In Britain, small rural ...

of around 1,500 residents about north-west of London, Stratford was a centre for the slaughter, marketing, and distribution of sheep, as well as for hide tanning and wool trading. Anti-Stratfordians often portray the town as a cultural backwater lacking the environment necessary to nurture a genius, and depict Shakespeare as ignorant and illiterate.

Shakespeare's father,

John Shakespeare

John Shakespeare (c. 1531 – 7 September 1601) was an English businessman in Stratford-upon-Avon and the father of William Shakespeare. He was a glover and whittawer ( leather worker) by trade. Shakespeare was elected to several municipal ...

, was a glover (glove-maker) and town official. He married

Mary Arden, one of the

Ardens of

Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a county in the West Midlands region of England. The county town is Warwick, and the largest town is Nuneaton. The county is famous for being the birthplace of William Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avon an ...

, a family of the local

gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest ...

. Both signed their names with a mark, and no other examples of their writing are extant. This is often used as an indication that Shakespeare was brought up in an illiterate household. There is also no evidence that Shakespeare's two daughters were literate, save for two signatures by

Susanna that appear to be "drawn" instead of written with a practised hand. His other daughter,

Judith, signed a legal document with a mark. Anti-Stratfordians consider these marks and the rudimentary signature style evidence of illiteracy, and consider Shakespeare's plays, which "depict women across the social spectrum composing, reading, or delivering letters," evidence that the author came from a more educated background.

Anti-Stratfordians consider Shakespeare's background incompatible with that attributable to the author of the Shakespeare canon, which exhibits an intimacy with court politics and culture, foreign countries, and

aristocratic

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word's ...

sports such as

hunting

Hunting is the human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/hide (skin), hide, ...

,

falconry

Falconry is the hunting of wild animals in their natural state and habitat by means of a trained bird of prey. Small animals are hunted; squirrels and rabbits often fall prey to these birds. Two traditional terms are used to describe a person ...

,

tennis

Tennis is a racket sport that is played either individually against a single opponent ( singles) or between two teams of two players each ( doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket that is strung with cord to strike a hollow rubber ball ...

, and

lawn-bowling. Some find that the works show little sympathy for upwardly mobile types such as John Shakespeare and his son, and that the author portrays individual commoners comically, as objects of ridicule. Commoners in groups are said to be depicted typically as dangerous mobs.

Education and literacy

The absence of documentary proof of Shakespeare's education is often a part of anti-Stratfordian arguments. The free

King's New School in Stratford, established 1553, was about half a mile (0.8 kilometres) from Shakespeare's boyhood home.

Grammar schools

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary school, ...

varied in quality during the Elizabethan era and there are no documents detailing what was taught at the Stratford school. However, grammar school curricula were largely similar, and the basic Latin text was standardised by royal decree. The school would have provided an intensive education in

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

grammar, the

classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

, and

rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

at no cost. The headmaster,

Thomas Jenkins, and the instructors were

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

graduates. No student registers of the period survive, so no documentation exists for the attendance of Shakespeare or any other pupil, nor did anyone who taught or attended the school ever record that they were his teacher or classmate. This lack of documentation is taken by many anti-Stratfordians as evidence that Shakespeare had little or no education.

Anti-Stratfordians also question how Shakespeare, with no record of the education and cultured background displayed in the works bearing his name, could have acquired the extensive vocabulary found in the plays and poems. The author's vocabulary is calculated to be between 17,500 and 29,000 words. No letters or signed manuscripts written by Shakespeare survive. The appearance of Shakespeare's six surviving authenticated signatures, which they characterise as "an illiterate scrawl", is interpreted as indicating that he was illiterate or barely literate. All are written in

secretary hand

Secretary hand is a style of European handwriting developed in the early sixteenth century that remained common in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries for writing English, German, Welsh and Gaelic.

History

Predominating before the dominance ...

, a style of handwriting common to the era,

[.] particularly in play writing, and three of them utilize

breviographs to abbreviate the surname.

Name as a pseudonym

In his surviving signatures William Shakespeare did not spell his name as it appears on most Shakespeare title pages. His surname was spelled inconsistently in both literary and non-literary documents, with the most variation observed in those that were written by hand. This is taken as evidence that he was not the same person who wrote the works, and that the name was used as a

pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name (orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individua ...

for the true author.

Shakespeare's surname was hyphenated as "Shake-speare" or "Shak-spear" on the title pages of 15 of the 32 individual

quarto

Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produc ...

(or ''Q'') editions of Shakespeare's plays and in two of the five editions of poetry published before the

First Folio

''Mr. William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies'' is a collection of plays by William Shakespeare, commonly referred to by modern scholars as the First Folio, published in 1623, about seven years after Shakespeare's death. It is cons ...

. Of those 15 title pages with Shakespeare's name hyphenated, 13 are on the title pages of just three plays, ''

Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father died ...

'', ''

Richard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Battl ...

'', and ''

Henry IV, Part 1

''Henry IV, Part 1'' (often written as ''1 Henry IV'') is a history play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written no later than 1597. The play dramatises part of the reign of King Henry IV of England, beginning with the battle at ...

''. The hyphen is also present in one

cast list and in six literary

allusion

Allusion is a figure of speech, in which an object or circumstance from unrelated context is referred to covertly or indirectly. It is left to the audience to make the direct connection. Where the connection is directly and explicitly stated (as ...

s published between 1594 and 1623. This hyphen use is construed to indicate a pseudonym by most anti-Stratfordians, who argue that fictional descriptive names (such as "Master Shoe-tie" and "Sir Luckless Woo-all") were often hyphenated in plays, and pseudonyms such as "Tom Tell-truth" were also sometimes hyphenated.

Reasons proposed for the use of "Shakespeare" as a pseudonym vary, usually depending upon the social status of the candidate. Aristocrats such as Derby and Oxford supposedly used pseudonyms because of a prevailing "

stigma of print The stigma of print is the concept that an informal social convention restricted the literary works of aristocrats in the Tudor and Jacobean age to private and courtly audiences — as opposed to commercial endeavors — at the risk of social disg ...

", a social convention that putatively restricted their literary works to private and courtly audiences—as opposed to commercial endeavours—at the risk of social disgrace if violated. In the case of commoners, the reason was to avoid prosecution by the authorities: Bacon to avoid the consequences of advocating a more

republican form of government

A republic () is a "sovereign state, state in which Power (social and political), power rests with the people or their Representative democracy, representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of gov ...

, and Marlowe to avoid imprisonment or worse after faking his death and fleeing the country.

Lack of documentary evidence

Anti-Stratfordians say that nothing in the documentary record explicitly identifies Shakespeare as a writer; that the evidence instead supports a career as a businessman and real-estate investor; that any prominence he might have had in the London theatrical world (aside from his role as a front for the true author) was because of his money-lending, trading in theatrical properties, acting, and being a shareholder. They also believe that any evidence of a literary career was falsified as part of the effort to shield the true author's identity.

Alternative authorship theories generally reject the surface meaning of Elizabethan and Jacobean references to Shakespeare as a playwright. They interpret contemporary satirical characters as broad hints indicating that the London theatrical world knew Shakespeare was a front for an anonymous author. For instance, they identify Shakespeare with the literary thief Poet-Ape in

Ben Jonson

Benjamin "Ben" Jonson (c. 11 June 1572 – c. 16 August 1637) was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for t ...

's poem of the same name, the socially ambitious fool Sogliardo in Jonson's ''

Every Man Out of His Humour

''Every Man out of His Humour'' is a satirical comedy written by English playwright Ben Jonson, acted in 1599 by the Lord Chamberlain's Men.

The play

The play is a conceptual sequel to his 1598 comedy ''Every Man in His Humour''. It was much l ...

'', and the foolish poetry-lover Gullio in the university play

''The Return from Parnassus'' (performed c. 1601). Similarly, praises of "Shakespeare" the writer, such as those found in the

First Folio

''Mr. William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies'' is a collection of plays by William Shakespeare, commonly referred to by modern scholars as the First Folio, published in 1623, about seven years after Shakespeare's death. It is cons ...

, are explained as references to the real author's pen-name, not the man from Stratford.

Circumstances of Shakespeare's death

Shakespeare died on 23 April 1616 in Stratford, leaving a signed will to direct the disposal of his large estate. The language of the will makes no mention of personal papers, books, poems, or the 18 plays that remained unpublished at the time of his death. In an

interlineation Interlineation is a legal term that signifies writing has been inserted between earlier language. It is commonly used to indicate the insertion of new language between previous sentences in a contract

A contract is a legally enforceable agree ...

, the will mentions monetary gifts to fellow actors for them to buy

mourning rings.

Any public mourning of Shakespeare's death went unrecorded, and no eulogies or poems memorialising his death were published until seven years later as part of the

front matter

Book design is the art of incorporating the content, style, format, design, and sequence of the various components and elements of a book into a coherent unit. In the words of renowned typographer Jan Tschichold (1902–1974), book design, "though ...

in the First Folio of his plays.

Oxfordians think that the phrase "our ever-living Poet" (an epithet that commonly eulogised a deceased poet as having attained immortal literary fame), included in the dedication to

Shakespeare's sonnets that were published in 1609, was a signal that the true poet had died by then. Oxford had died in 1604, five years earlier.

Shakespeare's funerary monument

The Shakespeare funerary monument is a memorial to William Shakespeare located inside Holy Trinity Church at Stratford-upon-Avon in Warwickshire, the church in which Shakespeare was baptised and where he was buried in the chancel two days afte ...

in Stratford consists of a demi-figure effigy of him with pen in hand and an attached plaque praising his abilities as a writer. The earliest printed image of the figure, in

Sir William Dugdale

Sir William Dugdale (12 September 1605 – 10 February 1686) was an English antiquary and herald. As a scholar he was influential in the development of medieval history as an academic subject.

Life

Dugdale was born at Shustoke, near Coles ...

's ''Antiquities of Warwickshire'' (1656), differs greatly from its present appearance. Some authorship theorists argue that the figure originally portrayed a man clutching a sack of grain or wool that was later altered to help conceal the identity of the true author. In an attempt to put to rest such speculation, in 1924

M. H. Spielmann published a painting of the monument that had been executed before the 1748 restoration, which showed it very similar to its present-day appearance. The publication of the image failed to achieve its intended effect, and in 2005 Oxfordian

Richard Kennedy proposed that the monument was originally built to honour John Shakespeare, William's father, who by tradition was a "considerable dealer in wool".

Case for Shakespeare's authorship

Nearly all academic Shakespeareans believe that the author referred to as "Shakespeare" was the same William Shakespeare who was born in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564 and who died there in 1616. He became an actor and shareholder in the

Lord Chamberlain's Men

The Lord Chamberlain's Men was a company of actors, or a "playing company" (as it then would likely have been described), for which Shakespeare wrote during most of his career. Richard Burbage played most of the lead roles, including Hamlet, Othe ...

(later the

King's Men), the

playing company

Play is a range of intrinsically motivated activities done for recreational pleasure and enjoyment. Play is commonly associated with children and juvenile-level activities, but may be engaged in at any life stage, and among other higher-functio ...

that owned the

Globe Theatre

The Globe Theatre was a theatre in London associated with William Shakespeare. It was built in 1599 by Shakespeare's playing company, the Lord Chamberlain's Men, on land owned by Thomas Brend and inherited by his son, Nicholas Brend, and gra ...

, the

Blackfriars Theatre

Blackfriars Theatre was the name given to two separate theatres located in the former Blackfriars Dominican priory in the City of London during the Renaissance. The first theatre began as a venue for the Children of the Chapel Royal, child acto ...

, and exclusive rights to produce Shakespeare's plays from 1594 to 1642. Shakespeare was also allowed the use of the

honorific

An honorific is a title that conveys esteem, courtesy, or respect for position or rank when used in addressing or referring to a person. Sometimes, the term "honorific" is used in a more specific sense to refer to an honorary academic title. It ...

"

gentleman

A gentleman (Old French: ''gentilz hom'', gentle + man) is any man of good and courteous conduct. Originally, ''gentleman'' was the lowest rank of the landed gentry of England, ranking below an esquire and above a yeoman; by definition, the ra ...

" after 1596 when his father was granted a

coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central ele ...

.

[.]

Shakespeare scholars see no reason to suspect that the name was a pseudonym or that the actor was a front for the author: contemporary records identify Shakespeare as the writer, other playwrights such as

Ben Jonson

Benjamin "Ben" Jonson (c. 11 June 1572 – c. 16 August 1637) was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for t ...

and

Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe (; baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), was an English playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the Elizabethan playwrights. Based upon the ...

came from similar backgrounds, and no contemporary is known to have expressed doubts about Shakespeare's authorship. While information about some aspects of Shakespeare's life is sketchy, this is true of many other playwrights of the time. Of some, next to nothing is known. Others, such as Jonson, Marlowe, and

John Marston, are more fully documented because of their education, close connections with the court, or brushes with the law.

Literary scholars employ the same

methodology

In its most common sense, methodology is the study of research methods. However, the term can also refer to the methods themselves or to the philosophical discussion of associated background assumptions. A method is a structured procedure for bri ...

to attribute works to the poet and playwright William Shakespeare as they use for other writers of the period: the historical record and

stylistic studies, and they say the argument that there is no evidence of Shakespeare's authorship is a form of fallacious logic known as ''

argumentum ex silentio'', or argument from silence, since it takes the absence of evidence to be evidence of absence. They criticise the methods used to identify alternative candidates as unreliable and unscholarly, arguing that their subjectivity explains why at least as many as 80 candidates

have been proposed as the "true" author. They consider the idea that Shakespeare revealed himself autobiographically in his work as a cultural

anachronism

An anachronism (from the Ancient Greek, Greek , 'against' and , 'time') is a chronology, chronological inconsistency in some arrangement, especially a juxtaposition of people, events, objects, language terms and customs from different time per ...

: it has been a common authorial practice since the 19th century, but was not during the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras. Even in the 19th century, beginning at least with

Hazlitt and

Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tuberculos ...

, critics frequently noted that the essence of Shakespeare's genius consisted in his ability to have his characters speak and act according to their given dramatic natures, rendering the determination of Shakespeare's authorial identity from his works that much more problematic.

Historical evidence

The historical record is unequivocal in ascribing the authorship of the Shakespeare canon to a William Shakespeare. In addition to the name appearing on the title pages of poems and plays, this name was given as that of a well-known writer at least 23 times during the lifetime of William Shakespeare of Stratford. Several contemporaries corroborate the identity of the playwright as an actor, and explicit contemporary documentary evidence attests that the Stratford citizen was also an actor under his own name.

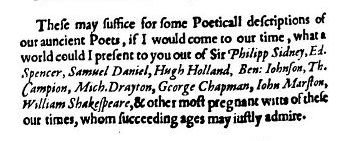

In 1598,

Francis Meres

Francis Meres (1565/1566 – 29 January 1647) was an English churchman and author. His 1598 commonplace book includes the first critical account of poems and plays by Shakespeare.

Career

Francis Meres was born in 1565 at Kirton Meres in the par ...

named Shakespeare as a playwright and poet in his ''

Palladis Tamia

''Palladis Tamia: Wits Treasury; Being the Second Part of Wits Commonwealth'' is a 1598 book written by the minister Francis Meres. It is important in English literary history as the first critical account of the poems and early plays of William ...

'', referring to him as one of the authors by whom the "English tongue is mightily enriched". He names twelve plays written by Shakespeare, including four which were never published in quarto: ''

The Two Gentlemen of Verona

''The Two Gentlemen of Verona'' is a comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1589 and 1593. It is considered by some to be Shakespeare's first play, and is often seen as showing his first tentative steps in laying ...

'', ''

The Comedy of Errors

''The Comedy of Errors'' is one of William Shakespeare's early plays. It is his shortest and one of his most farcical comedies, with a major part of the humour coming from slapstick and mistaken identity, in addition to puns and word play. It ...

'', ''

Love's Labour's Won

''Love's Labour's Won'' is a lost play attributed by contemporaries to William Shakespeare, written before 1598 and published by 1603, though no copies are known to have survived. Scholars dispute whether it is a true lost work, possibly a sequ ...

'', and ''

King John'', as well as ascribing to Shakespeare some of the plays that were published anonymously before 1598—''

Titus Andronicus

''Titus Andronicus'' is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy by William Shakespeare believed to have been written between 1588 and 1593, probably in collaboration with George Peele. It is thought to be Shakespeare's first tragedy and is often seen ...

'', ''

Romeo and Juliet

''Romeo and Juliet'' is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare early in his career about the romance between two Italian youths from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetim ...

'', and ''

Henry IV, Part 1

''Henry IV, Part 1'' (often written as ''1 Henry IV'') is a history play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written no later than 1597. The play dramatises part of the reign of King Henry IV of England, beginning with the battle at ...

''. He refers to Shakespeare's "sug

ed Sonnets among his private friends" 11 years before the publication of the

Sonnets

A sonnet is a poetic form that originated in the poetry composed at the Court of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in the Sicilian city of Palermo. The 13th-century poet and notary Giacomo da Lentini is credited with the sonnet's inventio ...

.

In the rigid

social structure

In the social sciences, social structure is the aggregate of patterned social arrangements in society that are both emergent from and determinant of the actions of individuals. Likewise, society is believed to be grouped into structurally rel ...

of Elizabethan England, William Shakespeare was entitled to use the honorific "gentleman" after his father's death in 1601, since his father was granted a coat of arms in 1596. This honorific was conventionally designated by the title

"Master" or its abbreviations "Mr." or "M." prefixed to the name

(though it was often used by principal citizens and to imply respect to men of stature in the community without designating exact social status). The title was included in many contemporary references to Shakespeare, including official and literary records, and identifies William Shakespeare of Stratford as the same William Shakespeare designated as the author. Examples from Shakespeare's lifetime include two official

stationers' entries. One is dated 23 August 1600 and entered by

Andrew Wise

Andrew Wise ( fl. 1589 – 1603), or Wyse or Wythes, was a London publisher of the Elizabethan era who issued first editions of five Shakespearean plays. "No other London stationer invested in Shakespeare as assiduously as Wise did, at least ...

and

William Aspley

William Aspley (died 1640) was a London publisher of the Elizabethan, Jacobean, and Caroline eras. He was a member of the publishing syndicates that issued the First Folio and Second Folio collections of Shakespeare's plays, in 1623 and 1632. ...

:

The other is dated 26 November 1607 and entered by

Nathaniel Butter

Nathaniel Butter (died 22 February 1664) was a London publisher of the early 17th century. The publisher of the first edition of Shakespeare's ''King Lear'' in 1608, he has also been regarded as one of the first publishers of a newspaper in Englis ...

and John Busby:

This latter appeared on the title page of ''

King Lear

''King Lear'' is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare.

It is based on the mythological Leir of Britain. King Lear, in preparation for his old age, divides his power and land between two of his daughters. He becomes destitute and insane an ...

'' Q1 (1608) as "M. William Shak-speare: ''HIS'' True Chronicle Historie of the life and death of King L

EAR and his three Daughters."

Shakespeare's social status is also specifically referred to by his contemporaries in Epigram 159 by

John Davies of Hereford

John Davies of Hereford (c. 1565 – July 1618) was a writing-master and an Anglo-Welsh poet. He referred to himself as ''John Davies of Hereford'' (after the city where he was born) in order to distinguish himself from others of the same nam ...

in his ''The Scourge of Folly'' (1611): "To our English

Terence

Publius Terentius Afer (; – ), better known in English as Terence (), was a Roman African playwright during the Roman Republic. His comedies were performed for the first time around 166–160 BC. Terentius Lucanus, a Roman senator, brought ...

Mr. Will: Shake-speare"; Epigram 92 by

Thomas Freeman in his ''Runne and A Great Caste'' (1614): "To Master W: Shakespeare"; and in historian

John Stow

John Stow (''also'' Stowe; 1524/25 – 5 April 1605) was an English historian and antiquarian. He wrote a series of chronicles of English history, published from 1565 onwards under such titles as ''The Summarie of Englyshe Chronicles'', ''The C ...

's list of "Our moderne, and present excellent Poets" in his ''Annales'', printed posthumously in an edition by Edmund Howes (1615), which reads: "M. Willi. Shake-speare gentleman".

After Shakespeare's death, Ben Jonson explicitly identified William Shakespeare, gentleman, as the author in the title of his eulogy,

"To the Memory of My Beloved the Author, Mr. William Shakespeare and What He Hath Left Us", published in the First Folio (1623). Other poets identified Shakespeare the gentleman as the author in the titles of their eulogies, also published in the First Folio:

"Upon the Lines and Life of the Famous Scenic Poet, Master William Shakespeare" by

Hugh Holland and

"To the Memory of the Deceased Author, Master W. Shakespeare" by

Leonard Digges.

Contemporary legal recognition

Both explicit testimony by his contemporaries and strong circumstantial evidence of personal relationships with those who interacted with him as an actor and playwright support Shakespeare's authorship.

The historian and antiquary

Sir George Buc served as Deputy Master of the Revels from 1603 and as

Master of the Revels

The Master of the Revels was the holder of a position within the English, and later the British, royal household, heading the "Revels Office" or "Office of the Revels". The Master of the Revels was an executive officer under the Lord Chamberlain. ...

from 1610 to 1622. His duties were to supervise and censor plays for the public theatres, arrange court performances of plays and, after 1606, to license plays for publication. Buc noted on the title page of ''George a Greene, the Pinner of Wakefield'' (1599), an anonymous play, that he had consulted Shakespeare on its authorship. Buc was meticulous in his efforts to attribute books and plays to the correct author, and in 1607 he personally licensed ''King Lear'' for publication as written by "Master William Shakespeare".

In 1602,

Ralph Brooke

Ralph Brooke (1553–1625) was an English Officer of Arms in the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. He is known for his critiques of the work of other members of the College of Arms, most particularly in ''A Discoverie of Certaine Errours Pu ...

, the

York Herald

York Herald of Arms in Ordinary is an officer of arms at the College of Arms. The first York Herald is believed to have been an officer to Edmund of Langley, Duke of York around the year 1385, but the first completely reliable reference to such a ...

, accused Sir

William Dethick

Sir William Dethick (c. 1542–1612) was a long-serving officer of arms at the College of Arms in London. He was the son of Sir Gilbert Dethick and followed his father as Garter Principal King of Arms. Though he was adjudged a qualified armor ...

, the

Garter King of Arms

The Garter Principal King of Arms (also Garter King of Arms or simply Garter) is the senior King of Arms, and the senior Officer of Arms of the College of Arms, the heraldic authority with jurisdiction over England, Wales and Northern Ireland. ...

, of elevating 23 unworthy persons to the

gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest ...

. One of these was Shakespeare's father, who had applied for arms 34 years earlier but had to wait for the success of his son before they were granted in 1596. Brooke included a sketch of the Shakespeare arms, captioned "Shakespear ye Player by Garter". The grants, including John Shakespeare's, were defended by Dethick and

Clarenceux King of Arms

Clarenceux King of Arms, historically often spelled Clarencieux (both pronounced ), is an officer of arms at the College of Arms in London. Clarenceux is the senior of the two provincial kings of arms and his jurisdiction is that part of Engla ...

William Camden

William Camden (2 May 1551 – 9 November 1623) was an English antiquarian, historian, topographer, and herald, best known as author of ''Britannia'', the first chorographical survey of the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, and the ''Annal ...

, the foremost antiquary of the time. In his ''Remaines Concerning Britaine''—published in 1605, but finished two years previously and before the Earl of Oxford died in 1604—Camden names Shakespeare as one of the "most pregnant witts of these ages our times, whom succeeding ages may justly admire".

Recognition by fellow actors, playwrights and writers

Actors

John Heminges

John Heminges (bapt. 25 November 1566 – 10 October 1630) was an actor in the King's Men, the playing company for which William Shakespeare wrote. Along with Henry Condell, he was an editor of the First Folio, the collected plays of Shakespeare ...

and

Henry Condell

Henry Condell ( bapt. 5 September 1576 – December 1627) was a British actor in the King's Men, the playing company for which William Shakespeare wrote. With John Heminges, he was instrumental in preparing and editing the First Folio, the col ...

knew and worked with Shakespeare for more than 20 years. In the 1623 First Folio, they wrote that they had published the Folio "onely to keepe the memory of so worthy a Friend, & Fellow aliue, as was our

Shakespeare, by humble offer of his playes". The playwright and poet Ben Jonson knew Shakespeare from at least 1598, when the Lord Chamberlain's Men performed Jonson's play ''

Every Man in His Humour

''Every Man in His Humour'' is a 1598 play by the English playwright Ben Jonson. The play belongs to the subgenre of the " humours comedy," in which each major character is dominated by an over-riding humour or obsession.

Performance and pu ...

'' at the

Curtain Theatre

The Curtain Theatre was an Elizabethan playhouse located in Hewett Street, Shoreditch (within the modern London Borough of Hackney), just outside the City of London. It opened in 1577, and continued staging plays until 1624.

The Curtain was ...

with Shakespeare as a cast member. The Scottish poet

William Drummond recorded Jonson's often contentious comments about his contemporaries: Jonson criticised Shakespeare as lacking "arte" and for mistakenly giving

Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

a coast in ''

The Winter's Tale

''The Winter's Tale'' is a play by William Shakespeare originally published in the First Folio of 1623. Although it was grouped among the comedies, many modern editors have relabelled the play as one of Shakespeare's late romances. Some criti ...

''. In 1641, four years after Jonson's death, private notes written during his later life were published. In a comment intended for posterity (''Timber or Discoveries''), he criticises Shakespeare's casual approach to playwriting, but praises Shakespeare as a person: "I loved the man, and do honour his memory (on this side Idolatry) as much as any. He was (indeed) honest, and of an open, and free nature; had an excellent fancy; brave notions, and gentle expressions ..."

In addition to Ben Jonson, other playwrights wrote about Shakespeare, including some who sold plays to Shakespeare's company. Two of the three

Parnassus plays

The Parnassus plays are three satiric comedies, or full-length academic dramas each divided into five acts. They date from between 1598 and 1602. They were performed in London by students for an audience of students as part of the Christmas fes ...

produced at

St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge founded by the House of Tudor, Tudor matriarch Lady Margaret Beaufort. In constitutional terms, the college is a charitable corpo ...

, near the beginning of the 17th century mention Shakespeare as an actor, poet, and playwright who lacked a university education. In ''The First Part of the Return from Parnassus'', two separate characters refer to Shakespeare as "Sweet Mr. Shakespeare", and in ''The Second Part of the Return from Parnassus'' (1606), the anonymous playwright has the actor

Kempe say to the actor

Burbage, "Few of the university men pen plays well ... Why here's our fellow ''Shakespeare'' puts them all down."

An edition of ''

The Passionate Pilgrim

''The Passionate Pilgrim'' (1599) is an anthology of 20 poems collected and published by William Jaggard that were attributed to " W. Shakespeare" on the title page, only five of which are considered authentically Shakespearean. These are two ...

'', expanded with an additional nine poems written by the prominent English actor, playwright, and author

Thomas Heywood

Thomas Heywood (early 1570s – 16 August 1641) was an English playwright, actor, and author. His main contributions were to late Elizabethan and early Jacobean theatre. He is best known for his masterpiece ''A Woman Killed with Kindness'', a ...

, was published by

William Jaggard

William Jaggard ( – November 1623) was an Elizabethan and Jacobean printer and publisher, best known for his connection with the texts of William Shakespeare, most notably the First Folio of Shakespeare's plays. Jaggard's shop was "at t ...

in 1612 with Shakespeare's name on the title page. Heywood protested this piracy in his ''Apology for Actors'' (1612), adding that the author was "much offended with M. Jaggard (that altogether unknown to him) presumed to make so bold with his name." That Heywood stated with certainty that the author was unaware of the deception, and that Jaggard removed Shakespeare's name from unsold copies even though Heywood did not explicitly name him, indicates that Shakespeare was the offended author. Elsewhere, in his poem "Hierarchie of the Blessed Angels" (1634), Heywood affectionately notes the nicknames his fellow playwrights had been known by. Of Shakespeare, he writes:

::Our modern poets to that pass are driven,

::Those names are curtailed which they first had given;

::And, as we wished to have their memories drowned,

::We scarcely can afford them half their sound. ...

::Mellifluous ''Shake-speare'', whose enchanting quill

::Commanded mirth or passion, was but ''Will''.

Playwright

John Webster

John Webster (c. 1580 – c. 1632) was an English Jacobean dramatist best known for his tragedies '' The White Devil'' and ''The Duchess of Malfi'', which are often seen as masterpieces of the early 17th-century English stage. His life and car ...

, in his dedication to ''

The White Devil'' (1612), wrote, "And lastly (without wrong last to be named), the right happy and copious industry of M. ''Shake-Speare'', M.

''Decker'', & M. ''Heywood'', wishing what I write might be read in their light", here using the abbreviation "M." to denote "Master", a form of address properly used of William Shakespeare of Stratford, who was titled a gentleman.

In a verse letter to Ben Jonson dated to about 1608,

Francis Beaumont

Francis Beaumont ( ; 1584 – 6 March 1616) was a dramatist in the English Renaissance theatre, most famous for his collaborations with John Fletcher.

Beaumont's life

Beaumont was the son of Sir Francis Beaumont of Grace Dieu, near Thrin ...

alludes to several playwrights, including Shakespeare, about whom he wrote,

::... Here I would let slip

::(If I had any in me) scholarship,

::And from all learning keep these lines as clear

::as Shakespeare's best are, which our heirs shall hear

::Preachers apt to their auditors to show

::how far sometimes a mortal man may go

::by the dim light of Nature.

Historical perspective of Shakespeare's death

The

monument to Shakespeare, erected in Stratford before 1623, bears a plaque with an inscription identifying Shakespeare as a writer. The first two Latin lines translate to "In judgment a Pylian, in genius a Socrates, in art a Maro, the earth covers him, the people mourn him, Olympus possesses him", referring to

Nestor,

Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

,

Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

, and

Mount Olympus

Mount Olympus (; el, Όλυμπος, Ólympos, also , ) is the highest mountain in Greece. It is part of the Olympus massif near the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea, located in the Olympus Range on the border between Thessaly and Macedonia, be ...

. The monument was not only referred to in the First Folio, but other early 17th-century records identify it as being a memorial to Shakespeare and transcribe the inscription. Sir William Dugdale also included the inscription in his ''Antiquities of Warwickshire'' (1656), but the engraving was done from a sketch made in 1634 and, like other portrayals of monuments in his work, is not accurate.

Shakespeare's will, executed on 25 March 1616, bequeaths "to my fellows John Hemynge

Richard Burbage

Richard Burbage (c. 1567 – 13 March 1619) was an English stage actor, widely considered to have been one of the most famous actors of the Globe Theatre and of his time. In addition to being a stage actor, he was also a theatre owner, ent ...

and Henry Cundell 26

shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence o ...

8

pence

A penny is a coin ( pennies) or a unit of currency (pl. pence) in various countries. Borrowed from the Carolingian denarius (hence its former abbreviation d.), it is usually the smallest denomination within a currency system. Presently, it is th ...

apiece to buy them

ourningrings". Numerous public records, including the royal patent of 19 May 1603 that

charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the rec ...

ed the King's Men, establish that Phillips, Heminges, Burbage, and Condell were fellow actors in the King's Men with William Shakespeare; two of them later edited his collected plays. Anti-Stratfordians have cast suspicion on these bequests, which were

interlined, and claim that they were added later as part of a conspiracy. However, the will was proved in the

Prerogative Court

In law, a prerogative is an exclusive right bestowed by a government or State (polity), state and invested in an individual or group, the content of which is separate from the body of rights enjoyed under the general law. It was a common facet of ...

of the

Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

(

George Abbot) in London on 22 June 1616, and the original was copied into the court register with the bequests intact.

John Taylor was the first poet to mention in print the deaths of Shakespeare and Francis Beaumont in his 1620 book of poems ''The Praise of Hemp-seed''. Both had died four years earlier, less than two months apart. Ben Jonson wrote a short poem "To the Reader" commending the First Folio engraving of Shakespeare by

Droeshout as a good likeness. Included in the prefatory

commendatory verse

The epideictic oratory, also called ceremonial oratory, or praise-and-blame rhetoric, is one of the three branches, or "species" (eidē), of rhetoric as outlined in Aristotle's ''Rhetoric'', to be used to praise or blame during ceremonies.

Origin ...

s was Jonson's lengthy eulogy "To the memory of my beloved, the Author Mr. William Shakespeare: and what he hath left us" in which he identifies Shakespeare as a playwright, a poet, and an actor, and writes:

::Sweet Swan of Avon! what a sight it were

::To see thee in our waters yet appear,

::And make those flights upon the banks of Thames,

::That so did take Eliza, and our James!

Here Jonson links the author to Stratford's river, the

Avon, and confirms his appearances at the courts of

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

and

James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

.

Leonard Digges wrote the elegy "To the Memorie of the Deceased Authour Maister W. Shakespeare" in the 1623 First Folio, referring to "thy Stratford Moniment". Living four miles from Stratford-upon-Avon from 1600 until attending Oxford in 1603, Digges was the stepson of Thomas Russell, whom Shakespeare in his will designated as overseer to the executors.

William Basse

William Basse (c.1583–1653?) was an English poet. A follower of Edmund Spenser, he is now remembered principally for an elegy on Shakespeare. He is also noted for his " Angler's song", which was written for Izaak Walton, who included it in '' ...

wrote an elegy entitled "On Mr. Wm. Shakespeare" sometime between 1616 and 1623, in which he suggests that Shakespeare should have been buried in

Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

next to

Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

, Beaumont, and Spenser. This poem circulated very widely in manuscript and survives today in more than two dozen contemporary copies; several of these have a fuller, variant title "On Mr. William Shakespeare, he died in April 1616", which unambiguously specifies that the reference is to Shakespeare of Stratford.

Evidence for Shakespeare's authorship from his works

Shakespeare's are the most studied secular works in history. Contemporary comments and some textual studies support the authorship of someone with an education, background, and life span consistent with that of William Shakespeare.

Ben Jonson and Francis Beaumont referenced Shakespeare's lack of classical learning, and no extant contemporary record suggests he was a learned writer or scholar. This is consistent with

classical blunders in Shakespeare, such as mistaking the

scansion

Scansion ( , rhymes with ''mansion''; verb: ''to scan''), or a system of scansion, is the method or practice of determining and (usually) graphically representing the metrical pattern of a line of verse. In classical poetry, these patterns are ...

of many classical names, or the anachronistic citing of

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

and

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

in ''

Troilus and Cressida

''Troilus and Cressida'' ( or ) is a play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1602.

At Troy during the Trojan War, Troilus and Cressida begin a love affair. Cressida is forced to leave Troy to join her father in the Greek camp. Meanwh ...

''. It has been suggested that most of Shakespeare's classical allusions were drawn from

Thomas Cooper's ''Thesaurus Linguae Romanae et Britannicae'' (1565), since a number of errors in that work are replicated in several of Shakespeare's plays, and a copy of this book had been bequeathed to Stratford Grammar School by John Bretchgirdle for "the common use of scholars".

Later critics such as

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

remarked that Shakespeare's genius lay not in his erudition, but in his "vigilance of observation and accuracy of distinction which books and precepts cannot confer; from this almost all original and native excellence proceeds". Much of the learning with which he has been credited and the omnivorous reading imputed to Shakespeare by critics in later years is exaggerated, and he may well have absorbed much learning from conversations. And contrary to previous claims—both scholarly and popular—about his vocabulary and word coinage, the evidence of vocabulary size and word-use frequency places Shakespeare with his contemporaries, rather than apart from them. Computerized comparisons with other playwrights demonstrate that his vocabulary is indeed large, but only because the canon of his surviving plays is larger than those of his contemporaries and because of the broad range of his characters, settings, and themes.

Shakespeare's plays differ from those of the

University Wits

The University Wits is a phrase used to name a group of late 16th-century English playwrights and pamphleteers who were educated at the universities ( Oxford or Cambridge) and who became popular secular writers. Prominent members of this group were ...

in that they avoid ostentatious displays of the writer's mastery of Latin or of

classical principles of drama, with the exceptions of co-authored early plays such as the ''Henry VI'' series and ''Titus Andronicus''. His classical allusions instead rely on the Elizabethan grammar school curriculum. The curriculum began with

William Lily's Latin grammar ''Rudimenta Grammatices'' and progressed to

Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caes ...

,

Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Ancient Rome, Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditiona ...

,

Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

,

Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

,

Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

,

Plautus

Titus Maccius Plautus (; c. 254 – 184 BC), commonly known as Plautus, was a Roman playwright of the Old Latin period. His comedies are the earliest Latin literary works to have survived in their entirety. He wrote Palliata comoedia, the gen ...

,

Terence

Publius Terentius Afer (; – ), better known in English as Terence (), was a Roman African playwright during the Roman Republic. His comedies were performed for the first time around 166–160 BC. Terentius Lucanus, a Roman senator, brought ...

, and

Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

, all of whom are quoted and echoed in the Shakespearean canon. Almost uniquely among his peers, Shakespeare's plays include references to grammar school texts and

pedagogy

Pedagogy (), most commonly understood as the approach to teaching, is the theory and practice of learning, and how this process influences, and is influenced by, the social, political and psychological development of learners. Pedagogy, taken as ...

, together with caricatures of schoolmasters. ''Titus Andronicus'' (4.10), ''

The Taming of the Shrew

''The Taming of the Shrew'' is a comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1590 and 1592. The play begins with a framing device, often referred to as the induction, in which a mischievous nobleman tricks a drunken ...

'' (1.1), ''

Love's Labour's Lost

''Love's Labour's Lost'' is one of William Shakespeare's early comedies, believed to have been written in the mid-1590s for a performance at the Inns of Court before Elizabeth I of England, Queen Elizabeth I. It follows the King of Navarre and ...

'' (5.1), ''

Twelfth Night

''Twelfth Night'', or ''What You Will'' is a romantic comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written around 1601–1602 as a Twelfth Night's entertainment for the close of the Christmas season. The play centres on the twins Vio ...

'' (2.3), and ''

The Merry Wives of Windsor

''The Merry Wives of Windsor'' or ''Sir John Falstaff and the Merry Wives of Windsor'' is a comedy by William Shakespeare first published in 1602, though believed to have been written in or before 1597. The Windsor of the play's title is a ref ...

'' (4.1) refer to Lily's ''Grammar''. Shakespeare also alluded to the

petty school that children attended at age 5 to 7 to learn to read, a prerequisite for grammar school.

Beginning in 1987,

Ward Elliott

Ward Elliott (August 6, 1937 – December 6, 2022) was an American political scientist who was the Burnet C. Wohlford Professor of American Political Institutions at Claremont McKenna College (CMC) in California. Elliot had been a professor at CMC ...

, who was sympathetic to the Oxfordian theory, and Robert J. Valenza supervised a continuing stylometric study that used computer programs to compare Shakespeare's stylistic habits to the works of 37 authors who had been proposed as the true author. The study, known as the Claremont Shakespeare Clinic, was last held in the spring of 2010. The tests determined that Shakespeare's work shows consistent, countable, profile-fitting patterns, suggesting that he was a single individual, not a committee, and that he used fewer relative clauses and more hyphens,

feminine endings, and

run-on lines than most of the writers with whom he was compared. The result determined that none of the other tested claimants' work could have been written by Shakespeare, nor could Shakespeare have been written by them, eliminating all of the claimants whose known works have survived—including Oxford, Bacon, and Marlowe—as the true authors of the Shakespeare canon.

Shakespeare's style evolved over time in keeping with changes in literary trends. His late plays, such as ''The Winter's Tale'', ''

The Tempest'', and

''Henry VIII'', are written in a style similar to that of other Jacobean playwrights and radically different from that of his Elizabethan-era plays. In addition, after the King's Men began using the Blackfriars Theatre for performances in 1609, Shakespeare's plays were written to accommodate a smaller stage with more music, dancing, and more evenly divided acts to allow for trimming the candles used for stage lighting.

In a 2004 study, Dean Keith Simonton examined the correlation between the thematic content of Shakespeare's plays and the political context in which they would have been written. He concludes that the consensus play chronology is roughly the correct order, and that Shakespeare's works exhibit gradual stylistic development consistent with that of other artistic geniuses. When backdated two years, the

mainstream chronologies yield substantial correlations between the two, whereas the

alternative chronologies proposed by Oxfordians display no relationship regardless of the time lag.

Textual evidence from the late plays indicates that Shakespeare collaborated with other playwrights who were not always aware of what he had done in a previous scene. This suggests that they were following a rough outline rather than working from an unfinished script left by an already dead playwright, as some Oxfordians propose. For example, in ''

The Two Noble Kinsmen

''The Two Noble Kinsmen'' is a Jacobean tragicomedy, first published in 1634 and attributed jointly to John Fletcher and William Shakespeare. Its plot derives from "The Knight's Tale" in Geoffrey Chaucer's ''The Canterbury Tales'', which had ...

'' (1612–1613), written with

John Fletcher, Shakespeare has two characters meet and leaves them on stage at the end of one scene, yet Fletcher has them act as if they were meeting for the first time in the following scene.

History of the authorship question

Bardolatry and early doubt

Despite adulatory tributes attached to his works, Shakespeare was not considered the world's greatest writer in the century and a half following his death. His reputation was that of a good playwright and poet among many others of his era.

Beaumont and Fletcher

Beaumont and Fletcher were the English dramatists Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, who collaborated in their writing during the reign of James I (1603–25).

They became known as a team early in their association, so much so that their joi ...

's plays dominated popular taste after the theatres reopened in the

Restoration Era in 1660, with Ben Jonson's and Shakespeare's plays vying for second place. After the actor

David Garrick

David Garrick (19 February 1717 – 20 January 1779) was an English actor, playwright, theatre manager and producer who influenced nearly all aspects of European theatrical practice throughout the 18th century, and was a pupil and friend of Sa ...

mounted the

Shakespeare Stratford Jubilee in 1769, Shakespeare led the field. Excluding a handful of minor 18th-century

satirical

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming or e ...

and

allegorical

As a literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a hidden meaning with moral or political significance. Authors have used allegory th ...

references, there was no suggestion in this period that anyone else might have written the works.

The authorship question emerged only after Shakespeare had come to be regarded as the English

national poet

A national poet or national bard is a poet held by tradition and popular acclaim to represent the identity, beliefs and principles of a particular national culture. The national poet as culture hero is a long-standing symbo ...

and a unique genius.

By the beginning of the 19th century, adulation was in full swing, with Shakespeare singled out as a transcendent genius, a phenomenon for which

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

coined the term "

bardolatry